Recording Ennui: My Journey from Skater to 4-Track Wizard (Part 1)

Read about how I escaped the pitfalls of 1990s suburbia, accidentally discovering tools I still use today as a recording artist. Note: I'm still adding to this, but you can read what I have so far

This is Part 1.

You will find Part 2, “The Day I Stopped 4-Tracking”, here.

You will find Part 3, “3 Methods of 4-Tracking”, here.

You will find Part 4, “Technical Notes on a Tiny Medium”, here.

I have 23 Cassettes from 1992-1996, Plus a Few from 2012.

Each tape is filled with 30-45 mins of original & inspired golden trash from my beginnings as a song maker.

NOTE TO SELF - RYNO, PLACE A 4-TRACK RECORDING HERE

A 4-Track History

For a period of time between 1992-1996, and again between 2011-2012, I was tracking music into a 4-Track–specifically the Yamaha MT-120.

1992-1996

The first chunk of time overlapped with my transition from high schooler (’94) to university student. 1994 marked the end of living in my parents’ home in Phoenix, followed by a single year in a run-down apartment on the edge of Scottsdale in 1995. This signaled the end of my youth in Arizona. I moved as a near-adult to Boulder, Colorado, in late 1995.

The bulk of my collaborative recording happened during the first two years, from 1992 to 1995, in Phoenix, Arizona. I primarily 4-tracked with my friend Shane, who would come over to play two or more times a week. I also recorded a lot with my brother Matthew and a close group of friends. We first connected through skateboarding, which was common in late 1988 and 1989, wearing out punk rock cassette tapes and ankles in the driveway. Most of us attended the same grade school, Madison Meadows, in Phoenix, but when high school began, our time together became fragmented due to our separation. We weren't all the same age, which is a common experience for early friendships, and this separation did impact our music-making.

Looking back, it was a bold move by my parents to let me keep a drum set and amps in the living room, where we could rock. They knew where we were, I suppose. Their allowance deserves awards. That was the key to all of this music-making: having a place to rock. The formation of this rumpus-rock-room was an extension of the already awesome spine ramp sessions in our driveway. I remember days when we’d do both—skate and then take a break to rock.

This might have been a reflection of my parents' peculiar nature, which took me a few years to unpack. My father never really said he liked my art, nor did he say much against it, and my mother was the same. Even today, my mother, who’s still rocking, couldn’t name a song of mine. Yet, I know my father aimed to be the “ultimate family man.” He had us involved in all kinds of sports, where he was the coach, rushing home from the courthouse to tell us, “There were two outs, and we’d be running on contact.

Despite the separation in schools, we still got together often to play. We had built a strong foundation; we didn’t need a plan. Plugging in was the plan. Someone could always conjure a riff, and sometimes a song would form and keep us going. We got together the same way we used to skateboard—just gathering and launching into action.

Boredom Isn’t Bad

I remember being desperately sick with boredom in suburban Arizona. The boredom was fed by teen angst, a kind of jet fuel. I cannot say things would be the same today because of the numerous distractions that smartphones and the Internet provide us. I miss this aspect of my youth the most. Time felt slower and endless. Tapes had to be rewound. We used to get together for no reason and create things without concern. These days, I feel more careful. This could be my own problem, I admit.

The creative act would go like this

For those of my readers wondering how to get started, this is how much of our music was made:

We got together often. That was key. We’d plug in and play anything. There was some concern about ‘wasting’ time learning cover songs. I don’t know if I stand by that thinking today, but doing ONLY covers is kinda soul destroying. We somehow knew our own invention was more important (however lousy). I couldn’t know then, what I know now, that this kind of inventiveness would pay off much later in immeasurable ways.

Back to the work. We’d play with an idea, for a bit. If we liked it, I’d hit record on a single mic room recording. Most of the time, we’d play to get the idea down and if it was good, maybe later we’d decide to track it out on a separate day.

Mic placement and volume was always a battle. Turning down was usually the key. I’d often put the mic in the center of the room, pointed at the drums. We’d just overwhelm the mic in a balanced way-to-loud kinda way. I didn’t know what was going on with that. Looking back, I know our amps were way too loud. I have memories of playing my drums and not being able to hear them over the noise. i can explain this desire to keep turning up, but I think it’s youth. “I can’t hear myself (turns up amp)”. Turning down didn’t make sense. Ha.

When we did have a couple ideas worthy of multitrack recording, or there was only 2 of us in the room, we’d try for an ‘initial tracks’ recording, possibly leave room for later layering of instruments/vocals. Usually multi-tracking was done be less people. All of us playing at once would defeat the purpose of getting separate instruments on separate channels. People also had to be home. Ultimately, much of the multi-tracking was done by me.

If it sounded good in the car stereo–it was good.

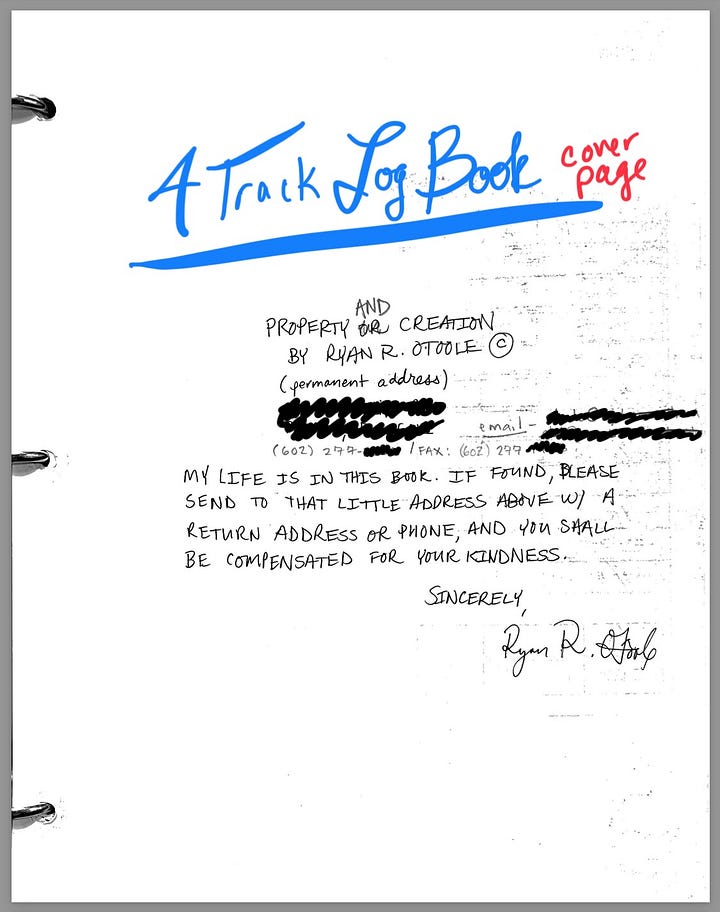

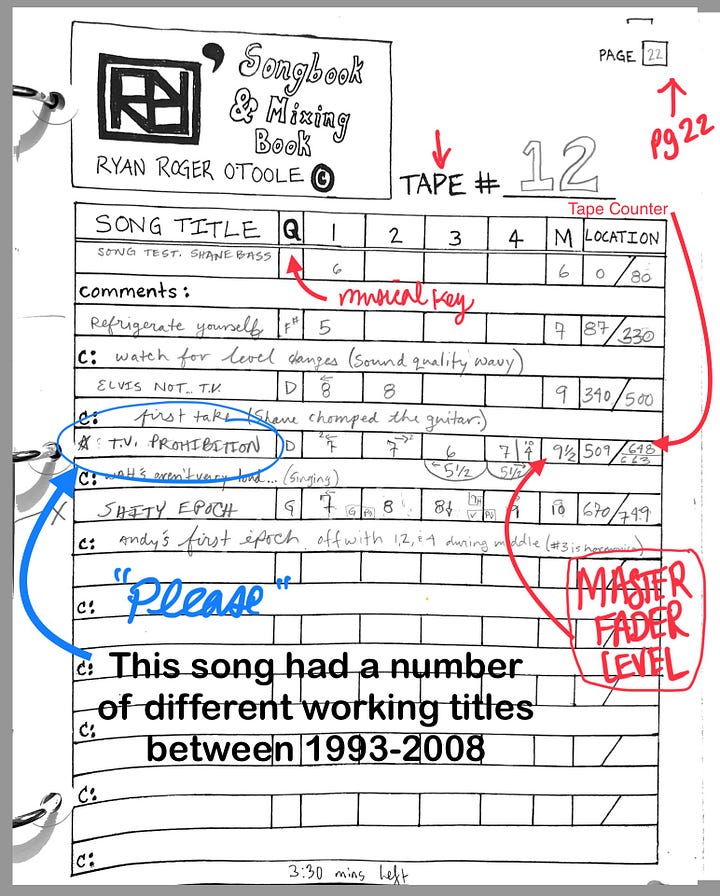

That’s a low bar right there. Ha. I got pretty good and making mixes for people to put into their car stereo–the ultimate test. Along with the tapes, I still have the original “Recording and Mixing” log book that I started back in 1990s. Check out the cover page (pictured above).

A hand written note on the first page of my 4-Track Log-Book

"My life is in this book. If found, please send to that little address above w/ a return address, or phone, and you shall be compensated for your kindness."

Great lessons learned from DIY Cassette 4-Tracking

Tracking to cassette is a real skill. Not much is different today, when it comes to planning out multi-track recording. However, the core lessons learned in 4-Tracking are pure and translate all the way up to working in Abbey Road, or somewhere swank.

Here are a few

When layering in instruments, you need a percussive cue to follow. This could be a click track, or the drums–therefore, initial tracks should always have drums or an audible time piece. A clean count in and counting during rests becomes a lifeline.

It takes longer to set up than it does to record. Getting levels right means spending time playing, then listening back. Sometimes moving the mic and turning down is the ballgame.

Scratch tracks, or reference/guide tracks that get recorder over in the end, make a great aid in matching emotion and feel. usually it’s the vocals, but it can also be talking, “Drum rest here, 4, 3, 2, 1”. This track would get recorded over.

Rehearsing the recording before recording makes for a better recording.

Having a plan on what goes on each of the 4 tracks, and when so, makes decisions on ‘type’ of sounds easier. Often times, the out of order tracking made things confusing.

It’s easy to say, because this was our only best option, but I’m glad I did so much 4-Track work in my teens and early twenties. I know it made me a better recording artist and songwriter.

Thank you for reading.

Please enjoy Part 2, “The Day I Stopped 4-Tracking”, here.

About the author

Ryan OToole (aka, RYNO) is a skateboarder from Arizona with too many film degrees, who writes songs for Pretty City Lights—a new music project based in Seoul, South Korea. His songs have been described as, "alternative rock for people dying of middle age". Formerly associated with the band, Amateur Blonde, his songs have been featured in television and film - notably, The Walking Dead (S10 Ep21). RYNO is the author of Behind The Lights a freemium substack publication, documenting the Pretty City Lights song & album creation process with the slogan, “watch me make music”.